The Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser is a widely misunderstood experiment. Apparently the common belief is that it's some kind of grand world-view-shattering mystery, with powers ranging from sending messages backwards in time (example pop-science article) to demonstrating the existence of conscious knowledge (example woo thread). Although there's continuous effort to correct these misconceptions, it's easy to run into them.

Case in point: I googled for "delayed choice quantum eraser" videos. The top result? This youtube video. It mashes a scene from the infamous What the #$*! Do We (K)now!? film into a scene from a terrible episode of "The Universe". Both clips mention backwards-in-time effects, and imply collapse is caused by humans looking in the general direction of an experiment. The forehead-slapping climaxes when a graphic literally shows a person turning waves into particles by opening their eyes (argh!).

Delayed choice erasure (hereafter DCQE) may be counter-intuitive, it may be interesting, but it's not mysterious or magical. We understand the math behind how it works. Interpretations of quantum mechanics explain it without any reference to consciousness or backwards-in-time effects.

In this post, my goal is to add to the pile of "DCQE is not magical" effort in some small way. I'll explain what you'd actually see if you ran a DCQE, show the same effects in a simplified model using qubits instead of photons, and hopefully convince that the common misconceptions are in fact misconceptions.

The Experiment

Your typical DCQE experiment is like a double-split experiment, except that an entangled copy of the which-slit-did-the-photon-go-through information is made. By later measuring the entangled copy of the information along the wrong axis, you can find some hidden interference patterns. The framing is that, by choosing to recover or discard the relevant information, you choose whether there was "really" an interference pattern or not.

Non-delayed quantum eraser experiments have a convenient place to store the which-slit information: in the photon's own polarization. That works great, except that a photon's polarization tends to be ... gone ... after the photon is absorbed. Allowing the which-way information to be measured later, long after the photon was absorbed, requires a different storage location.

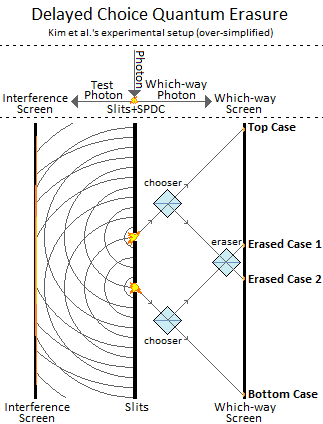

The best known DCQE experiment is the one performed by Kim et al in 2000. They stored the which-way information into the position of a second photon (by using a special crystal that splits photons into two photons). Wikipedia has a complicated diagram of the optical circuit they used, but I won't subject you to that. Instead, taking a a few liberties and some inspiration from one of the sites Wikipedia linked to, I made this alternative diagram of Kim et al's setup:

Be aware that the diagram is over-simplified. For example, the actual experiment has various lenses and prisms to direct the photons. Also, Kim et al didn't use screens; they used detectors connected to an electronic counter.

Anyways, let's go over the process the diagram is intended to communicate in a bit more detail:

Entangled Superposition: A photon arrives, encounters a wall with two slits, and passes through the slits. This puts the photon's position into a superposition. Special crystals then split the photon into two photons (with entangled positions, without breaking the superposition).

One of the resulting photons does the normal double-slit thing, building up an apparent lack-of-interference pattern on the interference screen. The other photon embodies the which-way information. Its journey is represented by the right half of the diagram, and can be delayed as long as desired.

Choice: The "choice" to erase is performed by two beam splitters (the "choosers"), one for the top slit and one for the bottom slit. If the which-way photon passes through the choosers without being reflected, its impact point at the top or bottom of the which-way screen tells us which slit the original photon passed through. But if the which-way photon is reflected by the choosers then, regardless of the starting slit, an "eraser" beam splitter will distribute the photon equally between the two erased cases.

Because both the top slit and bottom slit create a 50/50 split between the two erased cases (when erased), the which-way information is lost. It cannot be recovered.

(Side note: I think using controllable mirrors instead of beam splitters would impove the experiment, because using a beam splitter is a bit like making both choices instead of one choice.)

Recovery: Grouping runs of the experiment into "where the which-way photon hit" buckets reveals some interesting patterns. Within the bucket of test photons whose which-way photon went to the top case, no interference pattern is revealed. The same happens for the bottom case bucket. But the erased-case buckets filter the apparent lack-of-interference pattern we saw into two complementary interference patterns!

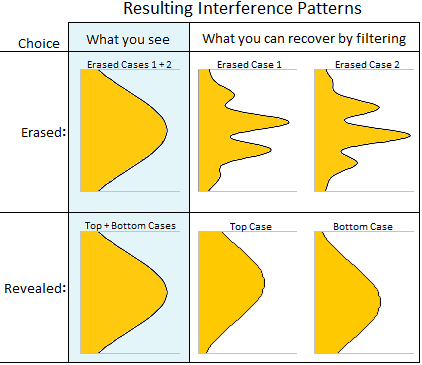

Here is a diagram (tweaked from one on wikipedia) summarizing what you would see on the interference screen if you ran this experiment, and also the implied pattern within each group (which you can recover only by filtering afterwards):

One crucial thing to notice about the above diagram is that you see the same thing in both the erased and revealed cases: a lack-of-interference pattern. You never directly see an interference pattern. The interference patterns are hidden, even in the erased cases. To find the hidden interference patterns, you need the apparently-useless which-way erased-case information. This happens because the two erased cases have complementary interference patterns: when you fail to separate them they get added together, and the ripples disappear.

(Side note: Technically, in Kim et al's setup, finding the "erased" or "revealed" subsets as shown in the diagram's 'What you see' column would also require filtering. That's because Kim et al use beam splitters instead of controllable mirrors to do the choosing. They can't control which choice was made; they have to deduce which choice happened based on where the which-way photon landed. However, because the erased and revealed plots look exactly the same as the total plot, you're not missing out on much.)

The 'What you can see' column of the diagram is my answer to anyone who thinks DCQE can perform faster-than-light communication "because Bob sees an interference pattern as soon as Alice erases the which-way information". Even when Alice erases the which-way information, Bob doesn't see an interference pattern. It's only when Alice and Bob get back together and compare notes, grouping Bob's results based on Alice's erasure measurement outcomes, that the hidden interference patterns can be revealed.

That's all I really have to say about the optical experiment. Let's try to simplify things a bit.

A Simplified Model

Performing DCQE does not inherently require light, and in my opinion thinking about it optically drags many unnecessary details along as baggage. DCQE is fundamentally not about photons, it is about quantum information and the odd things that happen when you try to copy it. As such, we should really be thinking in terms of qubits instead of in terms of photons. So let's translate this optical experiment into a quantum logic circuit operating on qubits.

In the optical experiment, a photon is placed into a superposition of going through the left slit or the right slit. This can be represented by a qubit: we'll call the qubit $A$, use $A = \ket{0}$ to mean "went through the left slit", and $A = \ket{1}$ to mean "went through the right slit". Easy. Just after passing through the slits, the photon's position is in the state $A = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{0} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{1}$.

Now the photon gets SPDC'd into two photons with the same position. Call the second photon $B$. The SPDC puts us into the state $AB = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{00} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{11}$. In other words, the positions of the two photons form an EPR pair. They are entangled.

The appearance of an interference pattern (or lack thereof) can also be translated from photons to qubits. The relevant common property is coherence. When a photon is coherent, it can interfere with itself. But a decohered photon won't interfere with itself. So we can think of DCQE as playing with whether or not a photon was coherent.

Qubits can also be coherent or decohered. When a qubit is coherent, it has a "preferred direction" corresponding to a point on the surface of the Bloch sphere. An experiment where you prepare a coherent qubit, then measure along the preferred direction, will give the same answer every time. A fully decohered qubit has no preferred direction; its state corresponds to the center of the Bloch sphere. No matter which axis you measure a fully decohered qubit along, your results will look like coin flips (but then you know its coherent state again).

It so happens that, because entanglement is suspiciously similar to measurement, qubits in an EPR pair appear to be fully decohered. It's only when you later compare results that you see they were coherent as a pair, instead of individually. DCQE is basically nothing but a reframing of this fact.

Concretely speaking, we're going to translate "does the photon make an interference pattern?" into "does measuring the qubit along different axes give probabilities other than 50/50?". We will run the qubit experiment many times, rotate Alice's qubit ($A$) by various amounts around the X axis, and see if the chance of getting ON when measuring $A$ in the computational basis stays at 50% or not. Because $A$ is part of an EPR pair, it will in fact stay at 50% and we will "conclude" that $A$ is decohered.

After "confirming" that $A$ is decohered, we will measure Bob's qubit ($B$, which was entangled with $A$). We'll group our measurements of $A$ into a $B$-was-OFF bucket and a $B$-was-ON bucket, and see if we can find some "hidden coherence". Two cases will be considered: one where Bob measures along an axis perpendicular to the ones Alice is using, and one where Bob just measures in the computational basis.

Here's what happens when Bob just measures in the computational basis:

As you can see above, initially Alice concludes that the input qubits are decohered because the measurement always acts like a 50/50 coin flip even as she tries various rotations around the X axis (i.e. she "doesn't see an interference pattern"). However, because Bob is measuring along a similar axis, and $A$ and $B$ form an EPR pair, his results are correlated with hers (more and less, as their measurement axies go into and out of alignment). So, when Alice groups $A$ based on Bob's results, she doesn't see a 50/50 split anymore. Given this, Alice concludes that her qubit was "secretly coherent" (i.e. she "revealed the hidden interference pattern").

(Side note: technically Alice is only checking axies in the YZ plane, and should also check the X axis before coming to conclusions about coherence. Just assume that she was promised that the input qubits would not be coherent in the X direction.)

Now for the "erased" case, where Bob measures along a perpendicular axis:

Bob's results are no longer correlated with Alice's, so grouping based on them doesn't give any predictive power. Alice concludes that her qubit was "really truly decohered".

You might have noticed I used a lot of "air-quotes" in this section. That's because basically all of the "conclusions" are misleading. They're a result of trying to force "$A$ and $B$ are entangled" into a false dichotomy between "$A$ was secretly coherent" and "$A$ was truly decohered". That's simply the wrong way to think about it. $A$ wasn't coherent, and it also wasn't decohered, it was simply entangled with $B$.

Misconception-causing explanations of DCQE have the exact same problem, they just use a took-one-path vs took-both-paths dichotomy instead of a coherence dichotomoy. If you check closely, you'll often find qualifiers like "IF you think the photon must have either taking one path or taken both paths" before the really crazy stuff. Which is technically correct... but demonstrably misleading. As soon as you drop the false dichotomy, and understand how entanglement is in play, the whole thing becomes kind of boring.

(Another issue in play is that we're not really "erasing" so much as "not revealing". If Bob measures along the wrong axis (or just doesn't measure at all), he doesn't learn information about Alice's result. He could have recovered the information needed to split Alice's results into two interesting cases, but he didn't. It seems really boring when framed that way.)

(A possibly better example of DCQE in terms of qubits comes from the state $\frac{1}{2} (\ket{000} + \ket{011} + \ket{101} + \ket{110})$. The third qubit tells you whether first two qubits are entangled to agree or entangled to disagree. Without conditioning on the correct axis of the third qubit, the first two qubits will fail any test of entanglement you throw at them. Basically, two entangled states can look exactly like an unentangled state... if you don't know which entangled state you're in. But covering this example would lead into discussions of entanglement swapping and why that works and this post is long enough, I think.)

Summary

You never see an interference pattern. The interference pattern only shows up when filtering after-the-fact, using the chooser's measurement results to group experimental runs.

Backwards-in-time effects aren't needed. Unless you insist on a false dichotomy that precludes entanglement being a thing. Common interpretations of quantum mechanics simply don't have that dichotomy. For example, in the Copenhagen interpretation, the observations are explained by the which-way photon's state being collapsed as soon as the test photon hits the screen (before the delayed choice).

Consciousness has nothing to do with this. The mathematical model simply makes no mention of anything besides the equipment. The experiment will have the same outcome whether or not a human is present.

(For example, consider that I just spent two thousand words explaining DCQE in detail, and the word "consciousness" only showed up in the context of common misconceptions. That wasn't on purpose. It just really isn't relevant.)

Most of the 'weird' is due to presentation. Ultimately all we're doing is either measuring the information needed to find the hidden interference patterns, or not. If you don't measure the needed information, you can't find the hidden patterns. Duh.

Comments

Isn't the big take away that the measurement (observer effect) isn't causing the collapse of the wave function, it is rather the possibility of having information or not having information that causes the collapse?

That is a useful insight to have, but I don't like to phrase it that way. I think people distort "possibility of having information" into wrong ideas like "Burning the paper the computer printed the result onto without looking at it takes away the possibility of having information, so the interference pattern should come back.".

One thing I want to try to communicate eventually, equivalent to what you're saying, is the concept of FOCUS ON THE COPIES. As long as an entangled copy of the information exists, no matter how obfuscated, there will be no self-interfering. Bringing back the self-interference requires un-making any copies. Un-making a copy is generally done by flawlessly running a copy-making process in reverse. Post-selection obscures the symmetry between making and un-making copies. Measurement is just thermodynamically-irreversible copy-making.

Kim's version of DCQE has a very simple set up, it was designed to rule out completely any sort of physical decoherence/interaction with the only variable left being the availability or not of information.....there's no mathematical equation to explain that... .of course this is not a physical one since it belongs to the cognitive realm...that's the spookiness on this....besides that, nonlocality can very well explain the apparent retro causality...

The video you are referring to is a layman's compilation of various top yt videos...so may I suggest a more explicit in terms of graphical cold explanation....then you might have a better grasp of why this experiment is so mind boggling....

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=u9bXolOFAB8

I would really appreciate your comments on Tom Campbells views as I feel your assertion that consciousness plays no role is pre-dated and still traps us into a pseudo materialists view. This is not a criticism, just a seeker searching for various and contrasting viewpoints so he can make his own mind up. Great work on the article in general. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_RwcGzGurc

@Peter Sage: My view of Tom Campbell is... not very positive. I think his proposed experiments are trivial and his predicted outcomes are incorrect.