Quantum networks are... let's call it interesting. Information can flow through them in surprising ways. To illustrate this point, I have made a puzzle.

The Puzzle

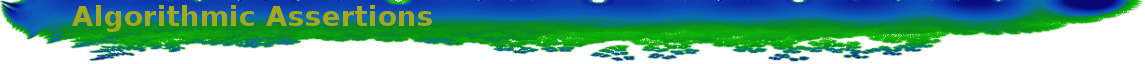

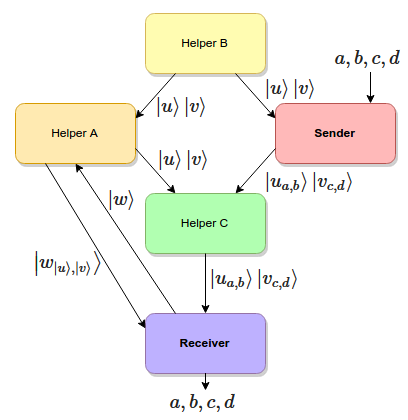

Consider the following network of quantum computers and quantum channels:

Each of the nodes in the diagram represents a quantum computer. Quantum computers can receive, process, introduce, and send qubits.

Each of the edges in the diagram represents a one-way quantum channel, and the number next to the edge is the number of times the channel can be used to send a single qubit. For example, two qubits can be sent over the channel from the Sender to Helper $C$, but only one qubit can pass over the channel from the Receiver to Helper $A$.

There is no pre-established entanglement between the nodes.

The goal is to find some way to pass four classical bits of information from the Sender to the Receiver, by processing qubits at each node, sending them along the given channels, and respecting the capacity constraints.

For example, sending two classical bits of information is easy. Just encode them in the obvious way, pass them from the Sender to Helper $C$ to the Receiver, and measure them.

Of course the actual solution is a bit trickier than that, so I'll give you some space.

Thinking Space

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

How about a hint? You can use superdense coding to transmit two classical bits over one quantum bit by consuming a Bell pair.

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

Another hint? Classical bits aren't the only things amenable to superdense coding.

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

Time's up!

Forced Moves

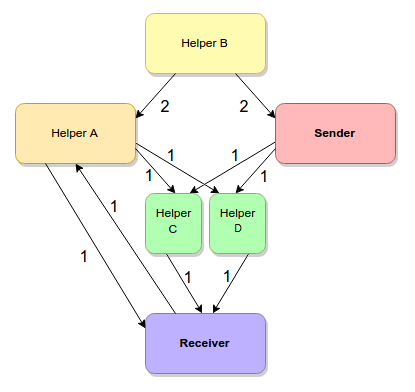

Before I explain my solution to this puzzle, let's go over some parts that are forced by common constraints.

The absolute maximum number of classical bits you can send per qubit is two (via superdense coding). The sender's outward capacity is two, and we have to send four bits, so we are forced to devote the sender's entire output capacity to superdense encoded bits.

Superdense coding requires a Bell pair. A sender needs to touch one half of the Bell pair to encode the message, and a receiver needs to end up with both halves of the pair to decode the message. The only place our Sender can get Bell pair halves, where the other half could conceivably end up at the Receiver, is from Helper $B$. So Helper $B$ must be creating two Bell pairs, which we'll call $u$ and $v$, and must be using the entire capacity of its channels to broadcast half of $u$ and $v$ to both the Sender and Helper $A$.

On the other side of the network, note that the Receiver has 3 inward capacity and 1 outward capacity. Also note that 3 is less than 4 (gasp!), and that without pre-existing entanglement the maximum number of classical bits you can receive per qubit is one. We're going to have to repurpose the outward quantum capacity as inward classical capacity. Namely, the Receiver is forced to create a Bell pair, which we will call $w$, and send one of $w$'s halves over its outward link.

With those forced moves noted, we find ourselves in this situation:

This is where I would have hit a wall, if I was solving this puzzle without knowing the trick ahead of time. We have to get $u$, $v$, $u_{a,b}$, and $v_{c,d}$ to the Receiver in order for superdense decoding to happen. That's four qubits to send, but only three qubits worth of capacity to receive. And three is less than four (oh my!).

But it turns out that superdense coding is a little more flexible than it seems.

Superdense Bell Pairs

I discovered the trick to solving this puzzle when thinking about something I mentioned in the previous post: that an entangled pair allows you to put a 4 coefficient unitary matrix into the shared system (in contrast to the normal 2 coefficient unit vector). I started wondering if there were applications for that, besides superdense coding.

The phase space of 2x2 unitary matrices can be parametrized as $U_{\phi,\theta,v} = e^{\phi i} \left( I i \cos{\theta} + \hat{v} \sigma_{xyz} \sin{\theta} \right)$, where $\phi$ and $\theta$ are angles and $\hat{v}$ is a unit vector in $\mathbb{R}^3$. We can ignore $\phi$, because global phase factors have no measurable effect. We can also fold $\theta$ into $\hat{v}$ to get a unit vector $\hat{v}_4$ in $\mathbb{R}^4$.

What that means is: we can probably encode an arbitrary real unit 4-vector into an entangled state. With some fiddling around, I determined that this could in fact be done and that you could decode the vector into amplitudes on the receiving side. Actually, the existing superdense coding process is already sufficient.

This is interesting. Being able to send a unit real 4-vector is an awful lot like being able to send two qubits. When you send two qubits, in the normal way, that's sending a unit 4-vector. It's just a complex unit 4-vector, instead of a real unit 4-vector.

So it seems like we could send qubits through superdense coding, as long as their phase information was limited to positive-vs-negative. We can't send arbitrary qubits, but we can send "flat" qubits.

But how often are qubits flat? Well... all the intermediate states of Grover's algorithm are flat. And quantum compression preserves flatness. But the most useful example I could think of was Bell pairs: qubits in the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (\ket{00} + \ket{11})$ don't require phase information, because their phase is uniformly zero (i.e. along the positive real line).

Correction (Jan 2016): I'm not sure how I ended up thinking only "flat" qubits could be dense-coded, but reading Aram Harrow's 2003 paper Coherent Communication of Classical Messages cleared things up. Superdense coding works on all qubits. The only catch is that the process creates an entangled copy of the qubits instead of moving the qubits.

So the first thing I tried was turning one shared Bell pair into two. I had the sender apply a Hadamard gate to two fresh qubits, putting them into the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (\ket{0} + \ket{1})$, then superdense-encoded them (as if they were classical bits) into an existing Bell pair half. After superdense-decoding on the other side, the resulting qubits were entangled with the sender's qubits. Two Bell pairs from one!... Except that we had to send a qubit and consume a Bell pair to do this, so it's a bit of a "two steps forward and one step back" situation. We could have just used the sent qubit to send a normal Bell pair half. There's probably cryptographic applications to using superdense coding in this way, but it's not useful in terms of channel capacity.

The next thing I tried was sending two Bell pair halves from a third party via superdense coding. I immediately ran into a problem: the superdense coding process doesn't move qubits into the entangled state, it copies them into the state. This is a problem, if you want to send a Bell pair half, because it makes a third half! This means your Bell pair isn't a Bell pair anymore, it's a GHZ state (i.e. three qubits in the state $\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (\ket{000} + \ket{111})$).

Why is having a GHZ state a problem? Well, it's a totally different thing! For example, you can't do superdense coding with a GHZ state spread over three parties. And in order to cancel a qubit out of a GHZ state, turning it back into a Bell pair, you need one of the other qubits in the state to be in the same place at the same time.

You might expect that the sender, who just created the extra copy, would have access to that copy and could use it to cancel out the original. However, because that copy is superdense encoded into a Bell pair, there's no way to extract it without both halves of the pair! If there was a way to do so, the receiver could immediately do it on their side (FTL communication would be possible).

Having the receiver do the cancelling would work, but then we'd have to spend channel capacity moving the garbage copy over. That would defeat the purpose of using superdense coding in the first place.

So the only way this could work is if some intermediate node... Oh. That's what Helper $C$ is for. To clean up the garbage!

Solution

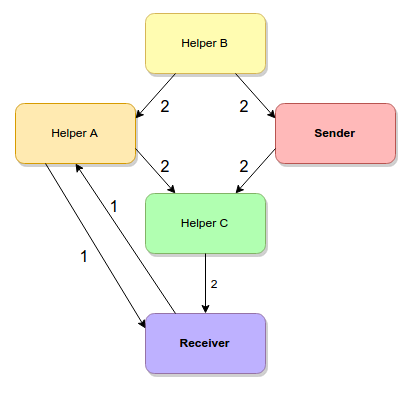

My solution to the puzzle goes as follows.

First, Helper $B$ creates two Bell pairs ($u$ and $v$) and broadcasts them to Helper $A$ and the Sender. The Sender gets one half of $u$ and one half of $v$. The other halves go to Helper $A$.

Also first, the Receiver creates a Bell pair $w$ and sends one half of it to Helper $A$.

Second, the Sender superdense-encodes 4 bits of classical information ($a$, $b$, $c$, and $d$) into $u$ and $v$. This creates $u_{a,b}$ and $v_{c,d}$, which the Sender sends to Helper $C$.

Also second, Helper $A$ superdense-encodes $u$ and $v$ into $w$. This creates $w_{u,v}$, but turns the copies of $u$ and $v$ still held by Helper $A$ into garbage. Helper $A$ forwards this garbage to Helper $C$. Helper $A$ also sends $w_{u,v}$ to the Receiver.

Helper $C$ cleans up the garbage by controlled-not-ing $u_{a,b}$ into $u$ and $v_{c,d}$ into $v$. This cancels the garbage $u$ and $v$ out, leaving behind qubits that happen to encode $b$ and $d$. Helper $C$ then forwards $u_{a,b}$ and $v_{c,d}$ to the Receiver.

Finally, the Receiver consumes its half of $w$ to superdense-decode $w_{u,v}$ into $u$ and $v$. It then consumes $u$ and $v$ to superdense-decode $u_{a,b}$ and $v_{c,d}$ into qubits that return $a$, $b$, $c$, and $d$ when measured.

Here's the network, with all of the edges annotated by the information passing over them:

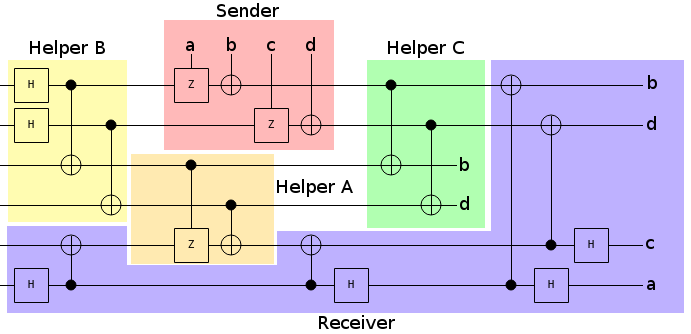

And here's a circuit diagram, showing the exact operations that are occurring. Each colored area corresponds to a node in the network diagram:

And that's how you can superdense encode Bell pairs and other "flat" qubits: by cleaning up the garbage created by that process.

Conclusions

Superdense coding works on qubits, but the qubits must have "flat" phases (e.g. no amplitudes with imaginary components) and the qubits are copied instead of moved.

Update

When I made the puzzle I was trying to exclude solutions that only used the normal type of superdense coding but, as noted by a commenter on hackernews, there is such a solution. Whoops!

Splitting the cleaner node into two pieces might fix the issue. Or maybe not! Give it a try:

Update 2

The solution can be improved, and the puzzle made harder, by using LOCC erasure to remove the extra entangled copies created by superdense coding the EPR pairs. This allows two of the communication links to be downgraded from quantum to classical. See this post for details.