There are many ways to prove that a quantum circuit does what you say it does. In this post, we're going to do that kind of proof in a somewhat unusual way.

We're going to prove that quantum teleportation works. Not by carefully considering how it affects input states, but by starting with a circuit that obviously moves a qubit from one place to another and then applying simple obviously-correct transformations until we end up with the quantum teleportation circuit.

Begin

We want to start with a trivial qubit-moving circuit. The simpler the better.

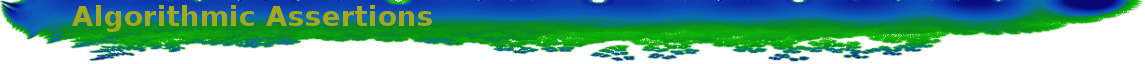

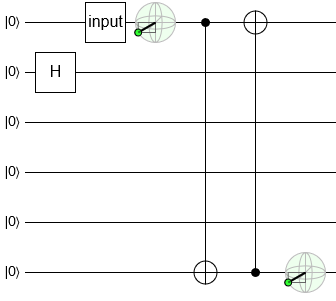

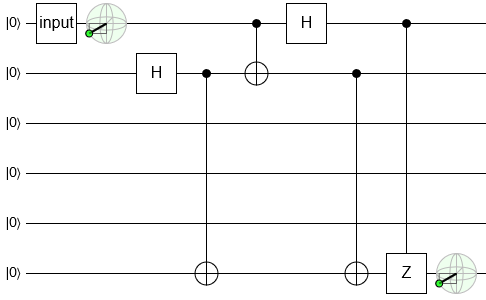

The simplest possible thing I can imagine for this task is to just use a swap gate. So that's what we'll do:

Note that the circuit diagrams are taller than necessary. It's just to make the move from top to bottom look like more of a journey. I've also included Bloch sphere state indicators as a visual hint that the circuit is in fact moving the qubit.

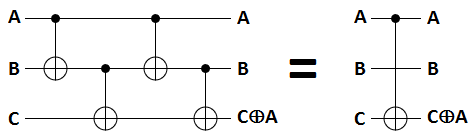

The first thing we need to do is break the swap gate into pieces we can work with. To do that, we're going to use a classical bit-twiddling trick: XOR swapping. XOR-swapping swaps two variables by XOR-ing them into each other three times:

#define SWAP(a, b) \

a^=b; \

b^=a; \

a^=b;

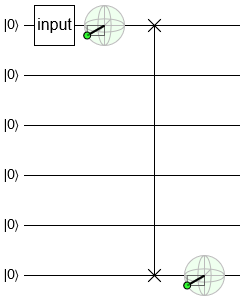

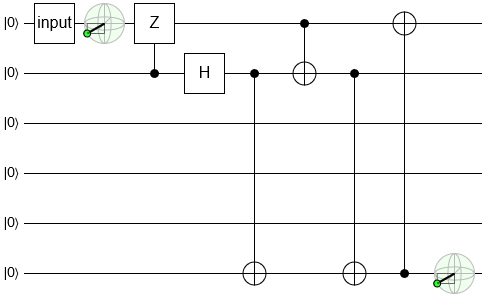

The CNOT gate is exactly a XOR-assignment (^=), and XOR-swapping works on qubits just as well as it does on bits, so we can replace our swap gate with three back-and-forth CNOTs:

Now we have some structure to work with.

Notice that the control of the first CNOT is on a wire that's OFF. That guarantees the CNOT will never fire. We can remove it:

I often find myself calling this back-and-forth CNOT pair a "move". It's like a swap, but only goes in one direction (and requires that the target qubit be zero'd).

At this point there's a huge number of routes we could take and it's not really clear what to do. That's why I consider these next two steps to be the key ones. They send us down an easy path.

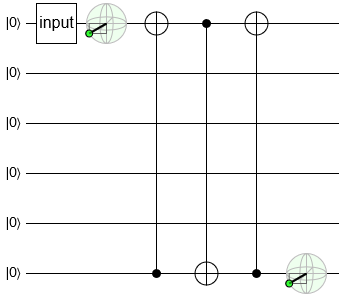

Note that we can do whatever we want to uninvolved wires. It won't affect the "move" part of our circuit. So, with a bit of foresight, let's add a Hadamard operation to the second wire:

That didn't really accomplish much, but it'll be useful after this next step.

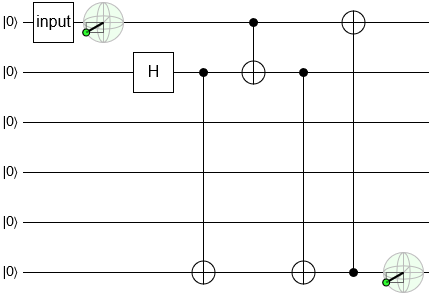

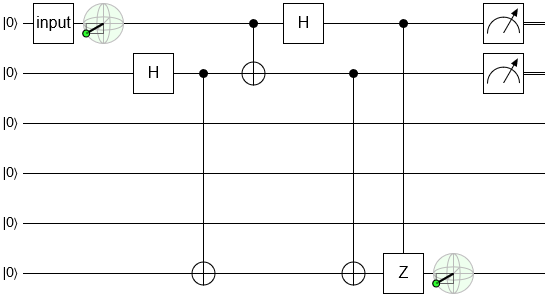

Imagine for a moment that we weren't allowed to jump all the way from the top qubit to the bottom qubit in one step. Instead, the top and bottom wires had to affect each other indirectly via the second wire. And, to make things even harder, suppose we didn't even know what state the second wire was in. Can we still toggle the bottom wire in a way controlled by the top wire?

Yes! We just do a classical trick I call "toggle forwarding":

We can't guarantee that the middle wire is ON or OFF, but we can force it to temporarily toggle. Then we do CNOTs onto the bottom wire controlled by the toggled and un-toggled middle wire.

When the top wire doesn't toggle the middle wire, the two bottom CNOTs cancel each other out. When the top wire is ON, then the middle wire does get toggled and exactly one of the bottom CNOTs will fire. That's how we get the top wire being ON to toggle the bottom wire, when forced to go through an unknown middle wire.

(Yes, this even works on qubits. Even when the middle qubit is entangled or in a state normally unaffected by NOT gates. No, really! Try it!)

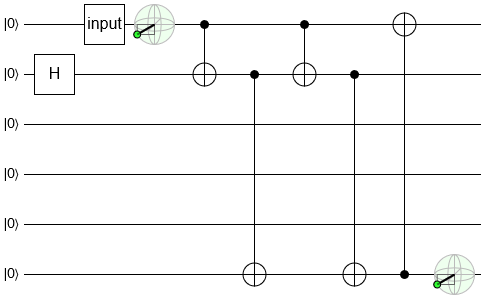

Applying this CNOT-via-intermediate construction to the downward part of our qubit-moving circuit produces this result:

That Hadamard we introduced is now on a wire that actually matters.

Here's our new short-term goal: get rid of that first CNOT. To that end, we slide the Hadamard gate rightward until it actually hops over said CNOT.

When a Hadamard hops over an X gate (a NOT), the X gets turned into a Z:

The controlled-NOT turned into a controlled-Z.

One of the useful things to know about controlled-Z gates is that it doesn't matter which wire is the control and which is the target.

Z gates don't do anything to qubits that are OFF, so you're conditioning on the target just as much as you are on the control.

Flipping the controlled-Z doesn't affect the function of the circuit:

Notice that the control is now the first thing second wire, and that the second wire starts out OFF.

Right, the control is never satisfied.

So the controlled-Z gate has no effect at all.

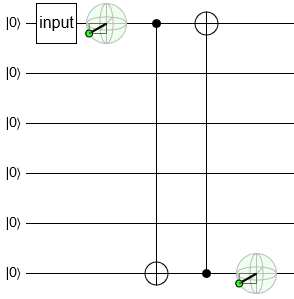

We can toss it:

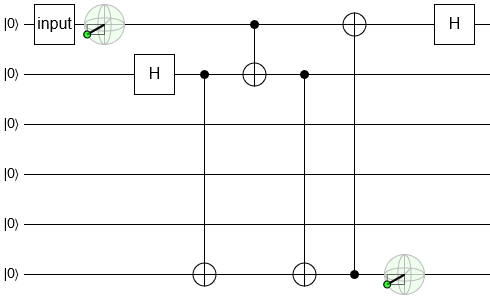

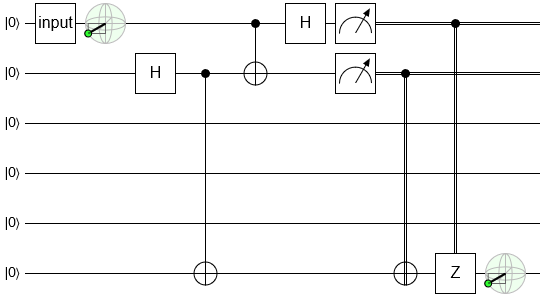

Now we need to do some work on the right side of the circuit.

Keep in mind that we only care about the state of the bottom qubit. We don't care if the other qubits get totally trashed; we can do whatever we want to them. As long as what we do doesn't affect the bottom qubit.

One way to guarantee we don't accidentally affect the bottom qubit is to only add operations on other wires, and only past the current end of the circuit. For example, we can add a Hadamard gate to the end of the top wire:

This Hadamard gate is going to be useful for nearly the same reason that the other one was.

We slide the new Hadamard gate leftward.

The only obstacle in its way is the controlled-NOT gate, but we easily hop over it and create a controlled-Z in the process:

Once again we flip the controlled-Z around:

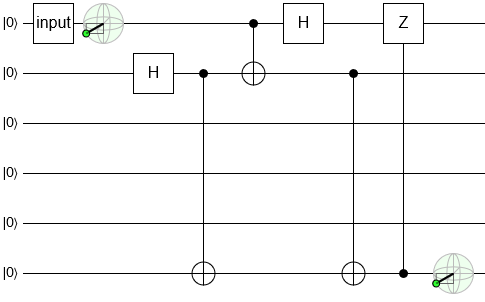

Notice that, with our latest circuit, the last two gates touch the top two wires but only for controls. This is a very big hint on what to do next: introduce measurements.

To guarantee these measurements don't affect the circuit, we add them after the end of the circuit on qubits that we don't care about:

Before we move on, I need to address the elephant in the room: spooky action at a distance. After all, when I mentioned this step to a person who engineers quantum computing hardware for a living, their reaction was "Wait, is that actually safe?".

A common trope in quantum mechanics is "When A and B are entangled, measuring A instantly affects B.". This spooky-action trope seems to contradict my assertion that measuring the top two wires can't affect the bottom wire. But actually there's no contradiction, just a slight difference in meaning.

When I say that measuring one qubit can't affect another, I'm talking about the expected outcomes of the circuit. I'm thinking in terms of what you know about the circuit's function ahead of time, when you don't condition on the measurement results.

When the spooky-action trope says that measuring one qubit might affect another, it is describing the fact that measuring a qubit can give you new information about the state of another qubit. The information you can learn just happens to be flexible in such a counter-intuitive way that people resort to describing the situation as one qubit instantaneously affecting another. Even though that's known to be a misleading analogy.

I hope that clarification was convincing, because we're about to make things worse by sliding the measurements leftward until they hop over the controls:

This step also doesn't affect the ahead-of-time-expected function of the circuit. Classical and quantum controls are equivalent. That fact is surprising enough that it has a name: the deferred measurement principle.

(I'd explain why this doesn't contradict delayed choice experiments, but I'd just be repeating the "spooky-action" explanation with different words.)

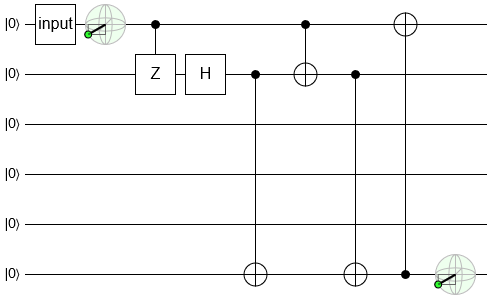

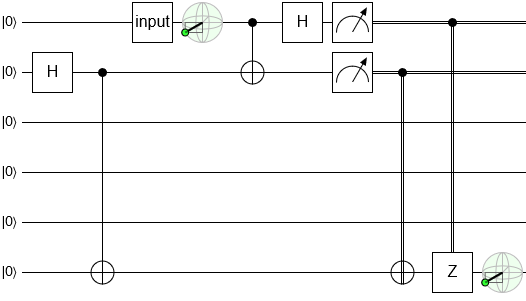

We only have one thing left to do: setup entanglement between the top and bottom before the input is known, instead of after. To do that we just slide the initial H gate and CNOT gate all the way to the left:

And that's it! Alice and Bob create an EPR pair, Alice picks a qubit to send, she does a Bell-basis measurement on that qubit and her EPR qubit, then she tells Bob the measurement results so he can apply appropriate corrective gates. The qubit is thereby communicated from Alice to Bob. Quantum teleportation.

Summary

You can turn a trivial qubit-swapping circuit into a quantum teleportation circuit by using a few classical xor tricks, doing whatever you want to wires that don't matter, hopping some Hadamards over NOTs, flipping a couple controlled-Zs, and knowing the deferred measurement principle.